Location

Wherever you are on Earth's surface, in order to describe your location, you need some point of reference. Right now you are probably reading this chapter at your computer. But where is your computer? It may set up in a certain place or you may be on a laptop computer, which means you can change where you are. In order to describe your location, you could name other items around you to give a more exact position of your computer. Or you could measure the distance and direction that you are from a reference point. For example, you may be sitting in a chair that is one meter to the right of the door. This statement provides more precise information for someone to locate your position within the room.

Similarly, when studying the Earth's surface, Earth scientists must be able to pinpoint any feature that they observe and be able to tell other scientists where this feature is on the Earth’s surface. Earth scientists have a system to describe the location of any feature. To describe your location to a friend when you are trying to get together, you could do what we did with describing the location of the computer in the room. You would give her a reference point, a distance from the reference point, and a direction, such as, "I am at the corner of Maple Street and Main Street, about two blocks north of your apartment." Another way is to locate the feature on a coordinate system, using latitude and longitude. Lines of latitude and longitude form a grid that measures distance from a reference point. You will learn about this type of grid when we discuss maps later in this chapter.

Direction

If you are at a laptop, you can change your location. When an object is moving, it is not enough to describe its location; we also need to know direction. Direction is important for describing moving objects.

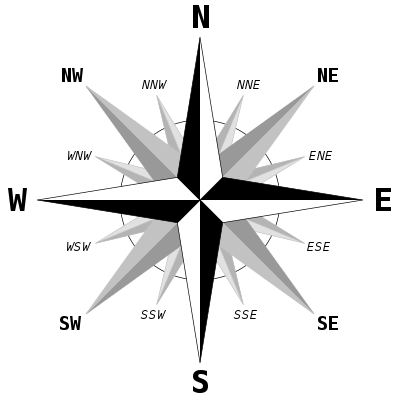

For example, a wind blows a storm over your school. Where is that storm coming from? Where is it going? The most common way to describe direction in relation to the Earth’s surface is by using a compass.

(Figure 2.1). The compass is a device with a floating needle that is a small magnet.

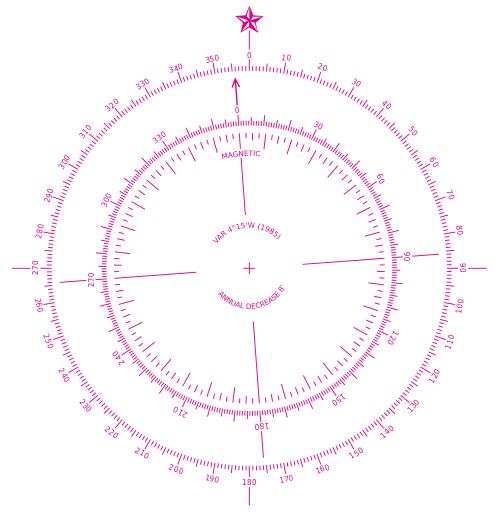

(Figure 2.2). The needle aligns itself with the Earth's magnetic field, so that the compass needle points to magnetic north. Once you find north, you can then describe any other direction, such as east, south, west, etc., on a compass rose (Figure 2.2).

(Figure 2.3) A compass needle aligns to the Earth's magnetic North Pole, not the Earth’s geographic North Pole or true north. The geographic North Pole is the top of the imaginary axis upon which the Earth’s rotates, much like the spindle of a spinning top. The magnetic North Pole shifts in location over time. Depending on where you live, you can correct for this difference when you use a map and a compass .

(Figure 2.4) When you study maps later, you will see that certain types of maps have a double compass rose to make the corrections between magnetic north and true north. An example of this type is a nautical chart that sailors and boaters use to chart their positions at sea or offshore

Figure 2.4: Nautical maps include a double compass rose that shows both magnetic directions (inner circle) and geographic compass directions (outer circle).

Topography

As you know, the surface of the Earth is not flat. Some places are high and some places are low.

For example, mountain ranges like the Sierra Nevada in California or the Andes mountains in South America are high above the surrounding areas.

(Figure 2.5) We can describe the topography of a region by measuring the height or depth of that feature relative to sea level .

You might measure your height relative to your best friend or classmate. When your class lines up, some kids make high "mountains" and others are more like small hills!What scientists call relief or terrain includes all the major features or landforms of a region. A topographic map of an area shows the differences in height or elevation for mountains, craters, valleys, and rivers.

Figure 2.6 The San Francisco Mountain area in northern Arizona as well as some nearby lava flows and craters. We will talk about some different landforms in the next section.

Landforms

(Figure 2.7),the Earth's surface and take away the water in the oceans , you will see that the surface has two distinctive features, continents and the ocean basins.

The continents are large land areas extending from high elevations to sea level. The ocean basins extend from the edges of the continents down steep slopes to the ocean floor and into deep trenches.

Both the continents and the ocean floor have many features with different elevations. Some areas of the continents are high. These are the mountains we have already talked about. Even on the ocean floor there are mountains! Let's discuss each.

Continents

Continents are relatively old (billions of years) compared to the ocean basins (millions of years). Because the continents have been around for billions of years, a lot has happened to them! As continents move over the Earth's surface, mountains are formed when continents collide. Once a mountain has formed, it gradually wears down by weathering and erosion.

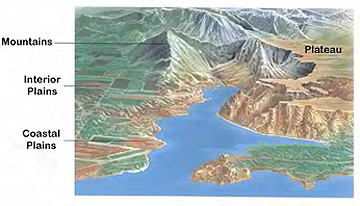

(Figure 2.8) Every continent has mountain ranges with high elevations . Some mountains formed a very long time ago and others are still forming today:

- Young mountains (<100 million years) – Mountains of the Western United States (Rocky Mountains, Sierra Nevada, Cascades), Mountains around the edge of the Pacific Ocean, Andes Mountains (South America), Alps (Europe), Himalayan Mountains (Asia)

- Old mountains (>100 million years) – Appalachian Mountains (Eastern United States), Ural Mountains (Russia).

Mountains can be formed when the Earth's crust pushes up, as two continents collide, like the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern United States and the Himalayas in Asia. Mountains can also be formed by a long chain of volcanoes at the edge of a continent, like the Andes Mountains in South America.

Over millions of years, mountains are worn down by rivers and streams to form high flat areas called plateaus or lower lying plains. Interior plains are in the middle of continents while coastal plains are on the edge of a continent, where it meets the ocean.

Figure 2.9: Summary of major landforms on continents and features of coastlines.As rivers and streams flow across continents, they cut away at rock, forming river valleys (Figure 2.9). The bits and pieces of rock carried by rivers are deposited where rivers meet the oceans. These can form deltas, like the Mississippi River delta and barrier islands, like Padre Island in Texas. Our rivers bring sand to the shore which forms our beaches.

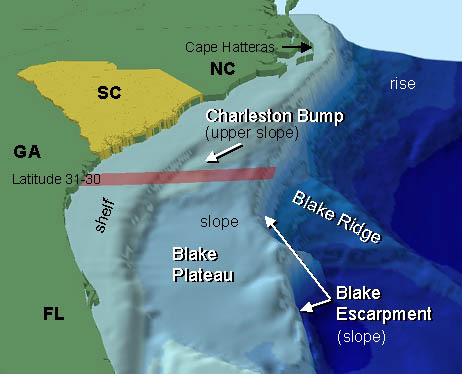

(Figure 2.10) The continental shelf usually goes out about 100 – 200 kilometers and is about 100-200 meters deep, which is a very shallow area of the ocean

From the edge of the continental shelf, the continental slope is the hill that forms the edge of the continent. As we travel down the continental slope, before we get all the way to the ocean floor, there is often a large pile of sediments brought from rivers, which forms the continental rise. The continental rise ends at the ocean floor, which is called the abyssal plain.

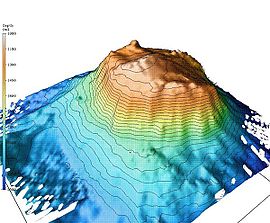

The ocean floor itself is not totally flat. Small hills rise above the thick layers of mud that cover the ocean floor. In many areas, small undersea volcanoes, called

seamounts

(Figure 2.11) rise more than 1000 m above the seafloor. Besides seamounts, there are long, very tall (about 2 km) mountain ranges that form along the middle parts of all the oceans.

(Figure 2.12) They are connected in huge ridge systems called mid-ocean ridges The mid-ocean ridges are formed from volcanic eruptions, when molten rock from inside the Earth breaks through the crust, flows out as lava and forms the mountains.

The deepest places of the ocean are the ocean trenches. There are many trenches in the world's oceans, especially around the edge of the Pacific Ocean.

(Figure 2.13) The Mariana Trench, which is located east of Guam in the Pacific Ocean, is the deepest place in the ocean, about 11 kilometers deep.

To compare the deepest place in the ocean with the highest place on land, Mount Everest is less than 9 kilometers tall. In these trenches, the ocean floor sinks deep inside the Earth. The ocean floor gets constantly recycled. New ocean floor is made at the mid-ocean ridges and older parts are destroyed at the trenches. This recycling is why the ocean basins are so much younger than the continents.

The Earth’s surface is constantly changing over long periods of time. For example, new mountains get formed by volcanic activity or uplift of the crust. Existing mountains and continental landforms get worn away by erosion.

Rivers and streams cut into the continents and create valleys, plains, and deltas. Underneath the oceans, new crust forms at the mid-ocean ridges, while old crust gets destroyed at the trenches. Wave activity erodes the tops of some seamounts and volcanic activity creates new ones. You will explore the ways that the Earth's surface changes as you proceed through this book.

Ocean Basins

The ocean basins begin where the ocean meets the land. The names for the parts of the ocean nearest to the shore still have the word “continental” attached to them because the continents form the edge of the ocean. The continental margin is the part of the ocean basin that begins at the coastline and goes down to the ocean floor. It starts with the continental shelf, which is a part of the continent that is underwater today.

(Figure 2.10) The continental shelf usually goes out about 100 – 200 kilometers and is about 100-200 meters deep, which is a very shallow area of the ocean

The ocean floor itself is not totally flat. Small hills rise above the thick layers of mud that cover the ocean floor. In many areas, small undersea volcanoes, called

seamounts

(Figure 2.11) rise more than 1000 m above the seafloor. Besides seamounts, there are long, very tall (about 2 km) mountain ranges that form along the middle parts of all the oceans.

(Figure 2.12) They are connected in huge ridge systems called mid-ocean ridges The mid-ocean ridges are formed from volcanic eruptions, when molten rock from inside the Earth breaks through the crust, flows out as lava and forms the mountains.

(Figure 2.13) The Mariana Trench, which is located east of Guam in the Pacific Ocean, is the deepest place in the ocean, about 11 kilometers deep.

To compare the deepest place in the ocean with the highest place on land, Mount Everest is less than 9 kilometers tall. In these trenches, the ocean floor sinks deep inside the Earth. The ocean floor gets constantly recycled. New ocean floor is made at the mid-ocean ridges and older parts are destroyed at the trenches. This recycling is why the ocean basins are so much younger than the continents.

The Earth’s surface is constantly changing over long periods of time. For example, new mountains get formed by volcanic activity or uplift of the crust. Existing mountains and continental landforms get worn away by erosion.

Rivers and streams cut into the continents and create valleys, plains, and deltas. Underneath the oceans, new crust forms at the mid-ocean ridges, while old crust gets destroyed at the trenches. Wave activity erodes the tops of some seamounts and volcanic activity creates new ones. You will explore the ways that the Earth's surface changes as you proceed through this book.